Orchard House

Welcome to Bath! You are probably here for the city’s history. And you’ve likely chosen to stay at Bath Backpackers having seen our reviews. You may have read things you like, but could also be put off by comments about the building: “everything creaks”, “old building” and “lots of stairs” - all accurate. What you probably don’t yet know is that this old place where you’ll be sleeping, eating and hanging out has fascinating connections - to Stonehenge and stalactites, horse hair and orchards, gambling and promiscuity, nuns and - of course - Jane Austen.

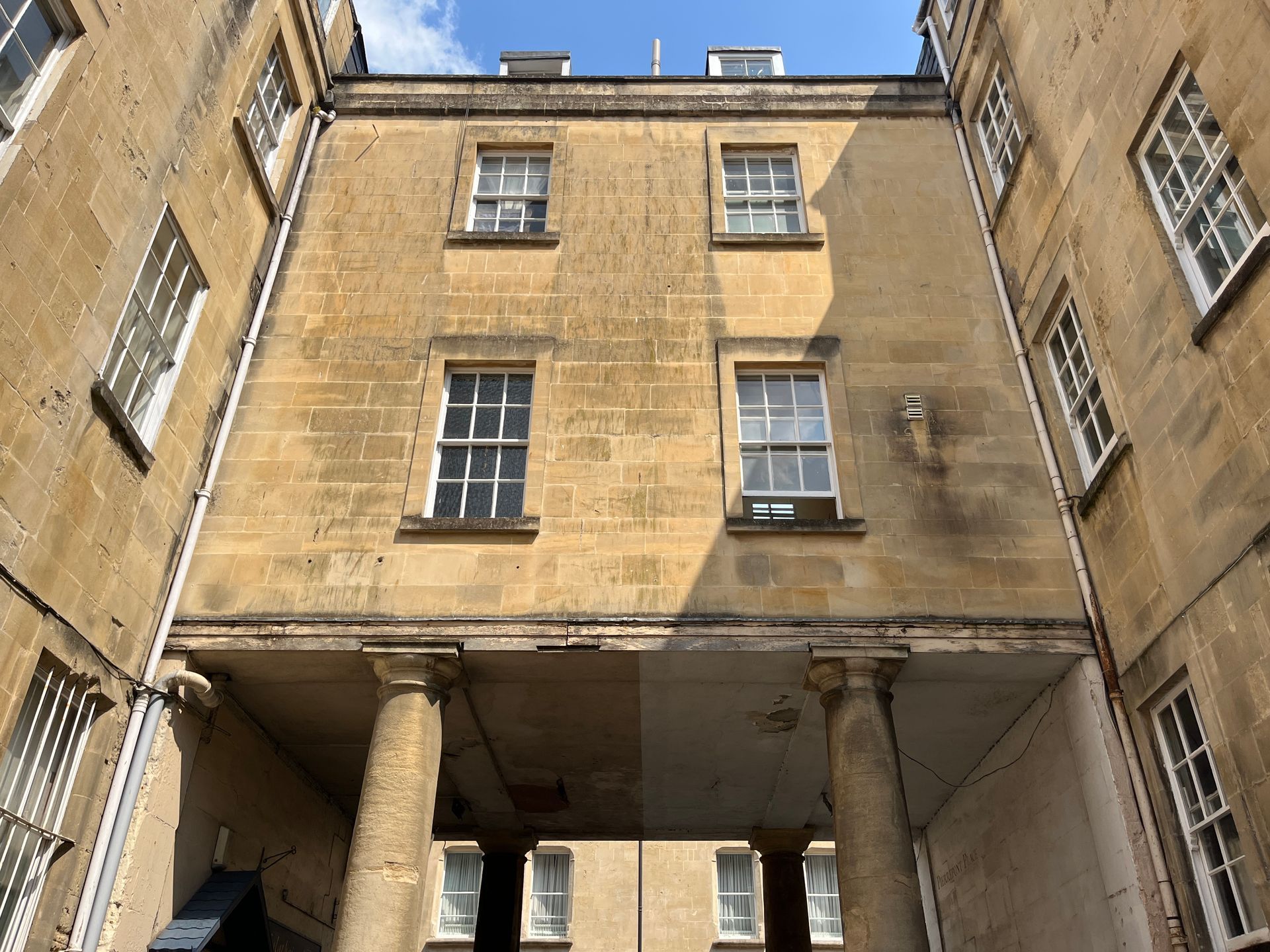

Ours is certainly an old building. 36 years older than the USA, it was built before Britain took India, Australia and other countries as colonies; before light bulbs, telephones or the steam engine were invented. Bristol and Liverpool were active slave trading ports at the time of construction. To be precise, the main house is 284 years old, while the archway (which the Kitchen sits above) is slightly younger, built 279 years ago.

Look above the front door, and you’ll see our building’s name: Orchard House. It is so called because originally it was in the orchard that belonged to the monks of Bath Abbey. If you pay for your stay by PayPal you’ll see that your payment is made out to Orchard House, Bath Ltd. When we took over the hostel, we considered renaming it from Bath Backpackers to Orchard House, but decided not to: Orchard House is a beautiful name, but Bath Backpackers is elegantly self-explanatory, so more helpful for guests.

John Wood the Elder built Orchard House in 1740 and the archway - called St James’ Portico - in 1745, in what is known as Palladian style. He is widely renowned as one of the masterplanners of Georgian Bath - “Georgian” means the period from 1714 to about 1837, and takes its name from the Kings George I, II, III and IV (that’s one to four in plain English). John Wood the Elder’s other Bath building projects include Queen Square, Prior Park and - arguably his masterpiece - The Circus, which he based on the dimensions of Stonehenge. Further afield he also built Bristol Exchange and Liverpool Town Hall. He’s known as ‘The Elder’ to distinguish him from his son John Wood the Younger, who built the Royal Crescent and Assembly Rooms.

Orchard House is located at 13 Pierrepont Street. The street was named after, and commissioned by, the English nobleman and landowner Evelyn Pierrepont, 2nd Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull. Before commissioning Pierrepont Street he spent ten years travelling in Europe, where he was known for gambling and “loose living” (which we think means he had sex with lots of different people, perhaps paying some of them). John Wood the Elder had grand plans for the terrace this house is part of, but he couldn’t get permission to build the Royal Forum of his dreams. So by the time Orchard House was finished, he grumpily declared it to be “a row of fifth-rate houses of the grander sort”.

Originally a residential property, folk memory has it that over time this place has been used as a home for nuns, a kebab shop, and even an illegal cannabis farm. But mostly it’s provided accommodation, and has been a hostel since the 1990s or possibly longer. Ask us if you’d like to see old photos from the 1990s, or from 2022 taken just before we started our renovations, when the aesthetic style was a heady mix of laddish cartoons, Mondrian art and hippy animals.

You’ll notice that all rooms on the ground and first floors have the very high ceilings typical of Georgian architecture. You might also hear noises between the rooms - some walls are thin, and apparently they are full of horse hair because that’s how places were built in England three hundred years ago. Solsbury and Dundas dorm rooms have beautiful fireplaces, partly hidden by bunk beds, which we may one day restore. And if you stay in Walcot or Solsbury dorms, you’re sharing space with what is called a ‘dumb waiter’ now hidden in the wall - this was a pulley device to move things between floors. We guess it was there to help remove the bed pans people would have used, so they could have a wee in the night without leaving their room - but that’s one thing we aren’t planning to reinstate!

Lots of Bath buildings have vaults like ours - check out bars and clubs Opium, Moles and Labyrinth. Our vaults were used to store the coal that was burned for heating and cooking - with the resulting soot turning the beautiful stone of Bath black (it’s since been deep cleaned, and coal banned). In the Vaults, you can spot several entry points that once were coal chutes. One day we might install a window in one of the coal chutes to give natural light down there - but we have other priorities first. When we moved in, the roof of the Vaults leaked badly, and our numerous buckets filled up rapidly with water. We’ve solved that problem - though you can still see some damage on the ceiling.

Our plumbing and electrics are old and we’re upgrading them slowly, starting with things that could be unsafe, and working our way on to improvements that will make the place more comfortable or more beautiful. We considered fitting showers upstairs but decided against it. We don’t have enough space and, crucially, the height of the building means that getting enough water pressure to the upper floors for more than a trickle of a shower would be really hard. So yes, if you’re staying in the dorm rooms Dundas, Walcot or Bathwick, you do indeed have to go down 65 stairs to reach the basement showers - and back up again.

When visiting the Roman Baths, you’ll see that mineral deposits have created beautiful features where the water has flowed for hundreds of years. Nearby Cheddar Gorge has amazing stalactites formed through a similar process. Because the water in Bath has seeped through the limestone of the Mendip plateau to the South, the city has very hard water, high in calcium. Some people prefer the taste of hard water to drink, but it means that all our plumbing is subject to limescale. The calcium and other minerals that make Cheddar Gorge beautiful create a white crust on our kettle, halt our washing machine, and narrow our pipes, causing blockages. We plan to fit a filter where the water mains enter our building, but that’s a specialist job we haven’t yet been able to do.

Orchard House is a listed building, meaning lots of rules exist about what we can and cannot do to upgrade or change it. There are three types of listed buildings in England: Grade 1 is for buildings of exceptional interest (like the Royal Crescent, the Circus, and Pulteney Bridge). Grade 2* is our status: it means our building is considered a “particularly important building of more than special interest”. And Grade 2 means “special interest” - some smaller Georgian terraces in Bath have this status. What is more, the city of Bath is - alongside Venice - one of just two places in the world where the whole city is designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This creates another layer of restrictions on what we can do here.

We imagined removing the wall between the Kitchen and Common Room to create one big space, but specialist guidance said we couldn’t do that as it would damage the integrity of the Common Room. According to a local heritage expert, “the panelling in the Common Room is considered a particularly good example of its kind and age and contributes very positively to the significance and special interest of the building, and to how the space of each room is perceived.” We read her report, spent time studying the Common Room, and changed our minds, eventually agreeing with her: the Common Room is a lovely space and its coherence should not be disrupted.

However, there are some restrictions we don’t agree with. We want to make the building more environmentally friendly - mainly to help it retain heat in winter, so we waste less energy and guests can be comfortable here. Our windows are the main source of heat loss, but we aren’t allowed to put in double glazing. Don’t get us wrong - we are very fond of our windows. Have a look at them in the hallways and kitchen - if you see panes where the glass looks a bit like it’s swimming, it means they are from before the Victorian era. Window panes that are over 200 years old! We love that. But hard choices must be made to stop people and the buildings we use from wasting the resources we have, so heat retention is more important than keeping the windows in an original or very old state.

We also can’t improve our creaky heating system by installing an air source heat pump - now considered the most ecological way of heating a building - because it would visually harm Bath’s harmonious architectural landscape. We are committed to being a part of Bath’s heritage and want to help preserve this, but we think it’s a global-level mistake to always prioritise heritage over ecology and believe that Britain’s national heritage policies will come to recognise this one day. We hope that day comes soon and that adaptation can be made as a choice, rather than forced upon us all by the even more dramatic changes in climate that are ahead.

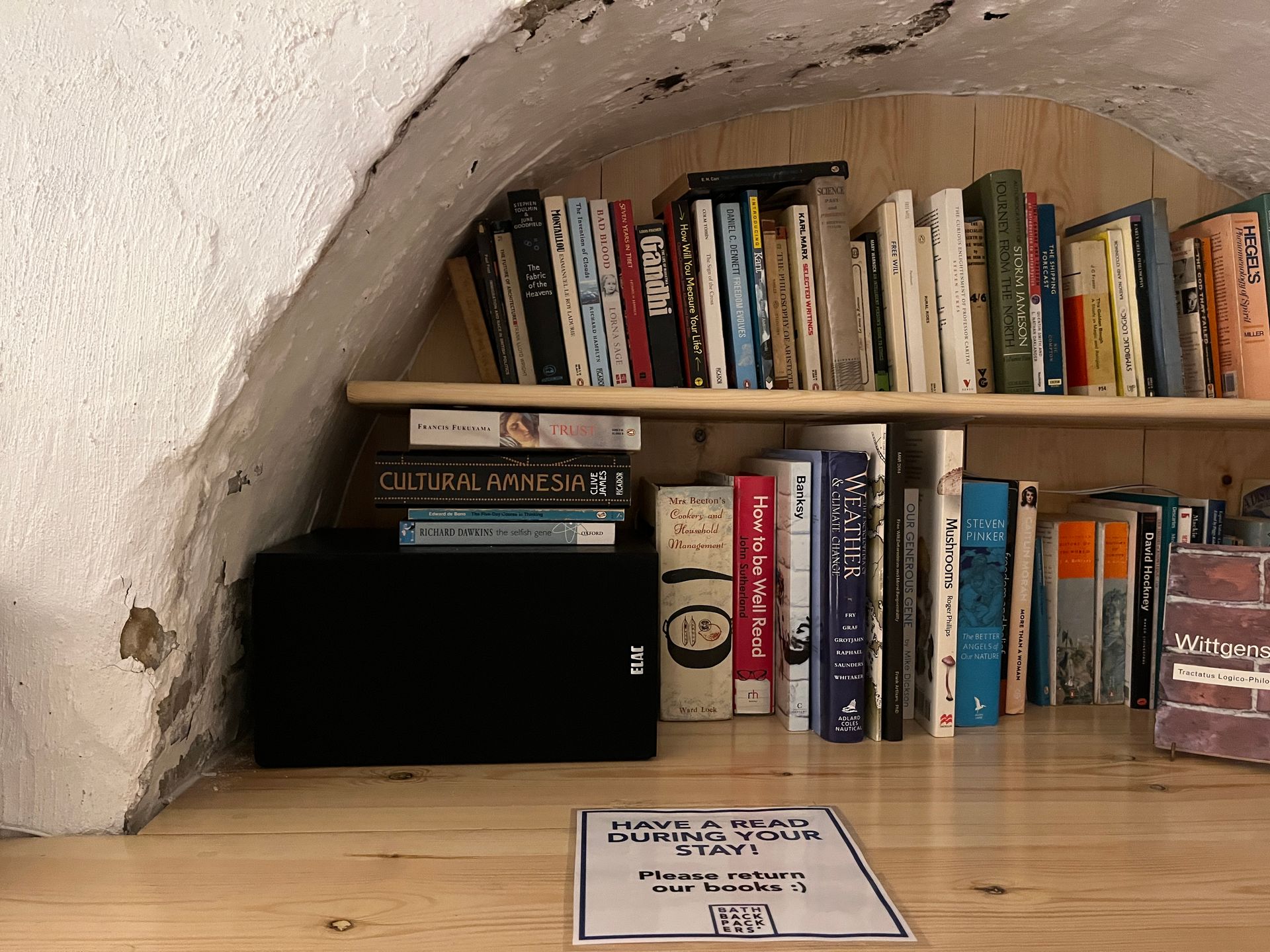

Back outside, St James’s Portico - described in its building listing as “an unusual and successful feature” - leads through to Pierrepont Place and Old Orchard Street, which remains a quirky little cobbled corner where a couple of boutique shops jostle for a piece of cuteness alongside the hotel bins. Further round, there’s a Masonic Hall which is open to the public on occasional afternoons (John Wood the Elder was probably a Mason). The Hall was previously Old Orchard Street Theatre and back in 1799, in this former incarnation, it was visited by Jane Austen, who wrote about it in her novel Northanger Abbey. You can borrow Northanger Abbey to read while you stay with us, and if you’d like to delve deeper into the themes we’ve explored here, you can also borrow from our selection of local history books in reception. Or check out the Mayor’s Guides - they are volunteers who offer free (yes, totally free!) guided tours of the city every day, which is a great way to learn more about Bath’s history, including the architecture of John Wood the Elder.

While dear old Orchard House will always present us and our visitors with inconveniences - lots of stairs, squeaky floors, peeling plaster - we hope you’ll enjoy its quirks and appreciate its long history as much as we do. We love hearing from guests about how you think we could improve things here, so please share your ideas. And if you can help persuade the people who make heritage rules to get with the ecological programme, then let’s talk!New Paragraph